While I still consider myself a Whovian, I haven’t watched “Nu Who” for several years. To put it succinctly, Chris Chibnall was Doctor Who’s worst showrunner ever, and Jodie Whitaker’s 13th Doctor has proven to be as unlucky as her numbering. That’s why I had some hope when Russell T Davies, the man who successfully revived the franchise in 2007, was announced to be returning, although I found the return of David Tennant to be a desperate gimmick to bait the show’s lost audience into coming back. Still, I was willing to give it a chance.

Not anymore.

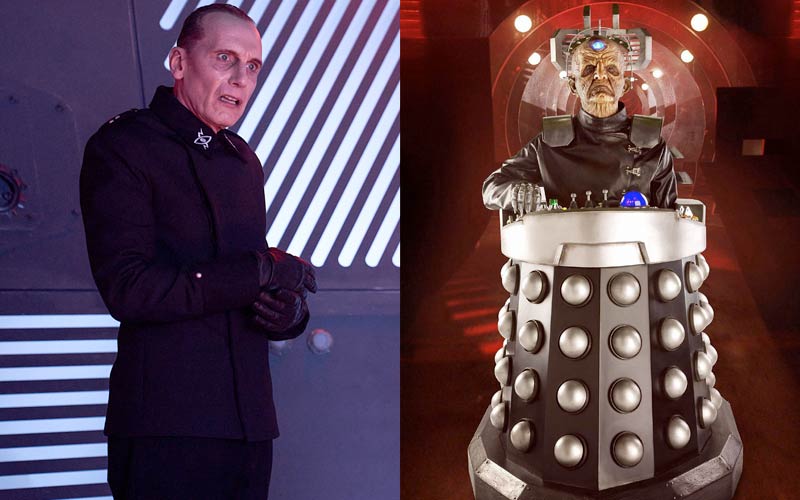

Recently, a Children in Need special was published on YouTube that shows an able-bodied and unscarred Davros, the iconic creator of the evil Daleks. While I thought the special’s comedic tone toward the “genesis of the Daleks” undermined the threat of the Doctor’s archenemies (a whole blog unto itself), fans, including myself, assumed Davros looked like this because it was a prequel, but Davies revealed this will be Davros’s look going forward.

We had long conversations about bringing Davros back, because he’s a fantastic character. Time and society and culture and taste have moved on, and there’s a problem with the old Davros: he’s a wheelchair user who is evil. I had problems with that. A lot of us on the production team did too, associating disability with evil. Trust me, there’s a very long tradition of this.

I’m not blaming people in the past at all, but the world changes. And when the world changes, Doctor Who has to change as well. So we made the choice to bring back Davros without the facial scarring and without the wheelchair – or his support unit, which functions as a wheelchair.

I say, this is how we see Davros now. This is what he looks like. This is 2023. This is our lens. This is our eye. Things used to be black and white; they’re not anymore. Davros used to look like that, and now he looks like this. We are absolutely standing by that.

Ignore Davies’ hypocrisy of create a villain who was motivated to make Cybermen so he could develop technology to get him out of a wheelchair. I’m here to show that he is missing the point.

It’s well-documented that the Daleks were inspired by the Nazis. These pseudo-cyborgs were created in the 1960s by filmmakers who still had fresh memories of World War II. Davros first appeared in 1975’s “Genesis of the Daleks,” which was written by Dalek creator Terry Nation. In keeping with the Nazi inspiration, Davros bears mannerisms often associated with Hitler and the SS. (In fact, he reminds me of Peter Sellers’s Dr. Strangelove, only not satirical). He is blind and disabled due to constant eugenic experiments he, in true mad scientist fashion, conducted on himself. This eventually led to the creation of the Daleks. In other words, Davros being confined to a wheelchair is a consequence of his attempts to make a master race.

The problem is Davies is concerned with optics. The image of a villain in a wheelchair, he fears, will make the audience assume all disabled people are evil. This ignores the clear origins of and creator intentions for Davros. His disability was self-inflicted and motivated by racial supremacy. So, by curing Davros to avoid “ableism,” Davies is removing the consequences of a far greater evil and disrespecting the creators who came before him. He has made a Nazi pastiche look more like the so-called “Aryan ideal.” Doesn’t this validate that evil ideology? Isn’t it, in some bizarre way, actually ableism?

If Davros must be able-bodied to avoid portraying disabled people as evil, then other iconic villains must be changed to remain consistent. Villains like:

- Doctor Doom, who has a disfigured face.

- The Weird Sisters of Macbeth, who are blind.

- Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm Street, who is a burn victim.

- Baron Harkonnen from Dune, who is morbidly obese.

- Darth Vader, who is a burn victim, an amputee, and an asthmatic.

In all of these cases, these disabilities are the consequences of their evil actions and often motivate the evils they are now committing. We fear them because they’re stark representations of the true face of evil and its consequences (and also the fear of the unnatural or abnormal, but that’s a blog for another day). Removing these disabilities fundamentally alters the characters to the point that they are no longer those characters. It also implies that only “perfect” or “able-bodied” people can be evil, trading one prejudice for another.

There are plenty of counterexamples with disabled heroes. Characters like Marvel’s Daredevil (blind), Zatoichi the blind swordsman, Jonah Hex (disfigured face), and even Spawn (burn victim). Characters like them either use or overcome their disabilities; their disabilities motivate them to be heroic. In other words, it boils down to virtue vs. vice. Contrary to popular belief, these are not exclusive to particular groups. As a Christian, I believe “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23), which means all people are on equal ground before the Almighty. Sadly, we will in times that deny this reality. Instead of understanding the deeper motivations and philosophies at work in disabled villains (and heroes), creators look only at the surface and/or see them as representative of entire groups of people instead of as representatives of themselves. It’s the definition of “shallow.”

All that to say, I won’t be watching the new Doctor Who anytime soon.