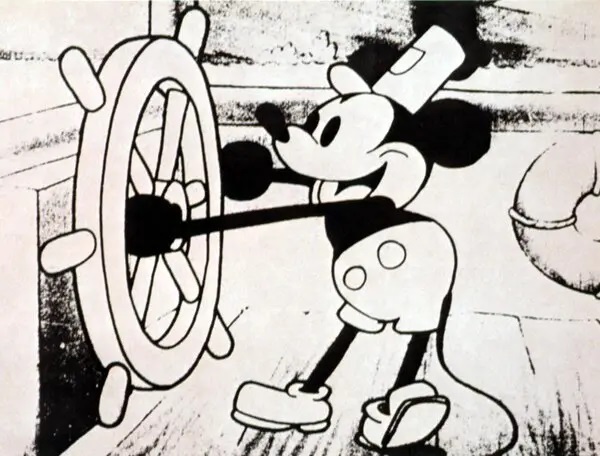

Perhaps I’m a bit late to the whole “public domain” discourse. It’s February, after all, and everyone is over “Steamboat Willie,” the 1928 Disney short that features the first appearance of Mickey Mouse, falling out of copyright protection. But as the first weeks of 2024 have passed and I’ve watched a ton of YouTube videos on physical media (thank you, Almighty Algorithm!), it’s brought to mind a lot of my thoughts on censorship and how it all connects to all of this.

The public domain is a double-edged sword. As a creator, I believe artists are entitled to copyright protection; it allows them to profit from their creations because that’s their trade. It’s no different than a fisherman who needs laws against stealing fish to maintain his livelihood. However, copyright in the United States has been extended to an almost absurd extent, with it now lasting 95 years. That’s well beyond the lifetime of (most) creators. Perhaps it can support his estate after his death, but that’s the most reasonable justification for such a timeframe.

The issue, I argue, is when mega-corporations get involved. They see their IP’s as only a means to make money, and they’ll be damned if they allow anyone but themselves to profit from them without permission. In the “old days,” actual people in these corporations needed to discover these unauthorized uses, but today it’s done through automation. That’s why YouTube bots constantly flag user content for copyright infringement. The problem is it ignores context and/or misidentifies the material in question. I know this firsthand because the remix I use as the theme song for my podcast, The Monster Island Film Vault, is now being flagged on YouTube as a completely different song by a record company I’ve never heard of. The whole system reeks of greed and even a bit of paranoia. In most cases, users are creative fans engaging with the content they love. They shouldn’t be punished for that. If anything, it’s free publicity for the studios.

Falling into public domain allows a piece of media to be used by anyone—which is both good and bad. On one hand, that can break an IP out of restrictive molds that have stagnated it or save it from mismanagement by the powers-that-be. (Just look at what Hollywood and other creative industries have been doing to beloved franchises the last 15 years or so). In some cases, it might be the only option to save something from ruin. I can tell you that I will jump at the opportunity to legally write and publish my own Superman stories in ten years since DC Comics likely won’t hire me. (I’ll leave it at that).

But, as a great man said, with great power comes great responsibility, and some creators have no business mucking around with public domain IPs. A.A. Milne’s beloved Winnie the Pooh books fell into public domain in 2022, and five seconds after that honey-eating bear was released into the wild, the movie Blood and Honey was revealed. Yes, a slasher flick about a guy wearing a Pooh mask. Now, sadly, it seems to have started a trend. On January 1, not one but two horror films “based” on “Steamboat Willie,” were announced: Mickey’s Mouse Trap and an “untitled horror-comedy.” There are also two survival horror video games in the works! I understand the creative drive to do something completely new with established characters. I can even understand the desire to stick it to Disney. But these? They strike me as uncreative and, at points, repugnant cash-grabs. Slasher movies, especially, are stupid-easy and require little thought. They flooded the market in the ‘80s and, with few exceptions, offered little value. Give someone a mask, a knife, and a bunch of top-heavy co-eds to chase and butcher, and you have instant “movie.” Boring. If a creator must make a horror film, why not lean into the unique features of the IP? For example, make “Steamboat Willie” a ferryman to the underworld. (You can have that one for free, writers!) Instead, they take the easy route. More than anything, though, this just seems corruptive. These are children’s icons, and these creators seem hellbent on destroying their innocence. I daresay it’s evil.

This brings me to the virtues of physical media. I’ll probably end up writing a whole other blog about this, but suffice it to say, in this case, it provides a means of protection and preservation for IPs in these culture war assaults. Unless Fahrenheit 451 happens and govern-controlled firemen are sent to people’s houses to collects books, DVD’s, and vinyl records to burn, those stories will remain as originally intended. No amount of censorship can completely destroy them. They can’t be removed or edited with a few keystrokes. Physical media, in a way, is like a halfway house between copyright and public domain. You’re granted a “share” in the ownership of something. Ownership grants you power. The power to control when, where, and how you partake of a story. The studios and publishers can’t decide that for you. It shows that you’re invested in the story, which will motivate you to protect it; it gives you skin in the game.

Is copyright a good thing? Yes. Is the public domain a good thing? Also, yes. But both can be abused. That’s why we must learn to use both wisely—but we’re in short supply of wisdom these days.

Perhaps we should cultivate that first.

Preferably, by reading some good books.

Did you find this information helpful? If you did, consider donating.