The beauty of WordPress is I can schedule a blog to be automatically posted, which is what I did with this one. I actually wrote it a few days ago. Why did I do this? Because I’m in the middle of the “fortnight from Hell” at my day job. (Long story).

Anyway, I grew up in a Christian home, so I’m well-versed in the Christian subculture. Honestly, the older I’ve gotten, the more annoyed I am with it. Not so much that I’ve rejected my faith (I think Christian faith and Christian culture are two completely different things and may as well be mutually exclusive), but enough to see how they usually don’t match up.

I’m going to focus only on one particular facet today: the idea that “Christian” is a genre.

This idea was initially sparked a year or so ago when I was talking with a friend on the phone who said she didn’t want to read my books because they weren’t “Christian enough.” As in, they wouldn’t fit into the Christian “genre” as defined by booksellers.

Christians, despite being commanded to go into the world and make disciples (Matt. 28:16-20), have for many years seemed intent on isolating themselves from the rest of the world and creating their own little culture complete with its own brand of entertainment. It goes all the way back to 1970s with the advent of “contemporary Christian music” thanks to the Jesus Movement. This has since expanded in other forms of media. Most recently, “faith-based films” such as God’s Not Dead have been popular the last few years.

While I have issues with the often poor artistic merits of many of these media (that’s a blog for another day), my biggest gripes with the so-called “Christian genre” are the mindsets it creates. First, it makes Christian culture very insular. I’ve known many fellow believers who refused to consume any media that wasn’t obviously Christian. In other words, listening to Carman was fine, but not Run-D.M.C. If it wasn’t didactic about faith, it was “too secular.” Some of it was even erroneously seen as satanic. These were things to be shielded against, especially when it came to kids (it’s always about the children, isn’t it?). So, new media was created by Christians for Christians. Considering the aforementioned often poor quality of their substitutes, it’s no wonder many Christians in the last 30-40 years grew up with bad senses of what makes good art. (Not to mention Christian creators were making obvious rip-offs of “secular” entertainment long before the Asylum. Anyone else remember the Spine Chillers Mysteries books?). It created an “us vs. them” mentality. It was about being “safe” and avoiding risky ideas that might challenge one’s faith.

Second, as I’ve already hinted at, it made “Christian” into a genre. Demon Hunter wasn’t just a metal band; they were a “Christian” metal band. (For the record, Demon Hunter is a genuinely great band). Like any genre, this automatically establishes the intended audience and the content (which, as I’ve noted, was often didactic and subpar). The problem is that “Christian” shouldn’t be a genre. It should be a philosophy, a worldview. Do atheists and other religions turn their beliefs into genres for the sake of marketing? For the most part, no. (Although some may do so in response to “Christian” stuff or as satire). In the history of literature, Christian authors didn’t concern themselves with whether their stories fit nicely into a “Christian genre”; they just told their stories. Think about how classics like Moby-Dick by Herman Melville or Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky or The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien (did you really think I’d get through this without mentioning my all-time favorite book?) if they were published in today’s environment in Christian publishing. I have a feeling they’d either be rejected by Christian publishers or watered down in the editing process.

“Christian,” as I’ve said, is a worldview, not a genre. It’s something that, when done correctly, flows naturally into a creator’s work because it’s a part of him. Art is an expression of its creator, so it’s impossible for him to not imbue it with how he sees the world. But, as I’ve said for years, story must be king. The moment someone starts sermonizing in his story, whether it’s about religion or environmentalism or whatever, it brings the story down. The storyteller will lose his audience. Heck, even kids will see through that.

Readers and critics will discuss themes and ideas when dissecting a story, but they usually don’t do something like label Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game “Mormon fiction.” Those elements are part of that book because they’re part of Card. To tell his story honestly, he had to write it that way. He wasn’t trying to proselytize anyone. I know that to my fellow Christian creators that might sound crazy, even sacrilegious, but I believe your witness can be helped by not being didactic with your stories.

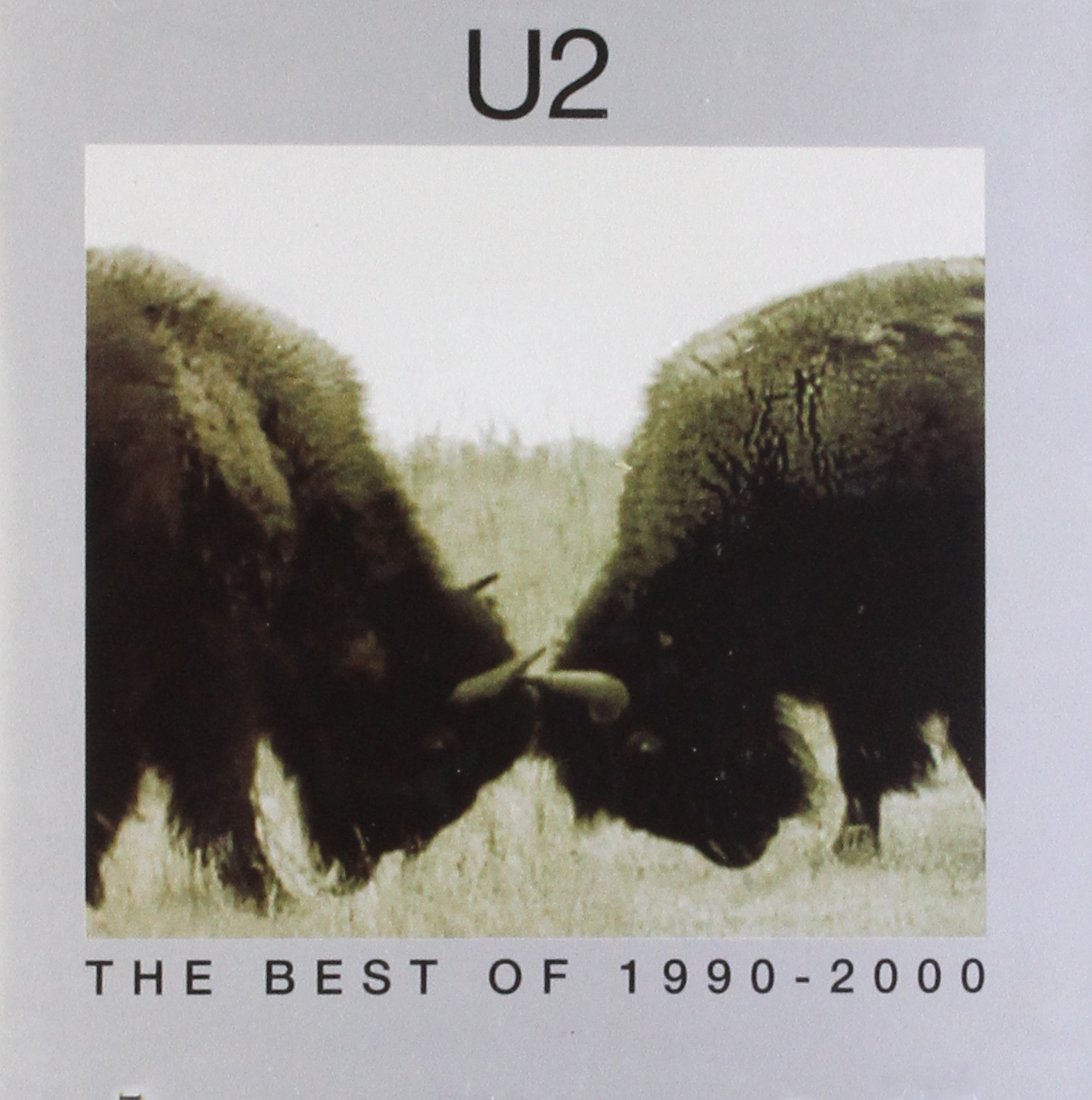

I’ve been listening to U2’s Greatest Hits albums while writing this blog. U2 is a Christian band (specifically, they’re Irish Catholic). Even a casual listen to their music makes that obvious. They don’t hide or flaunt that. They make their music and let it impact people. Jesus said you can know someone by their fruit (Matt. 7:15-20). That fruit doesn’t need to have “Apple” written on it for people to know what it is.

If you’d like to hear more about this, I highly recommend listening to these episodes of the Derailed Trains of Thought podcast hosted by my friends Nick Hayden and Timothy Deal: Episode 57: And the Moral of the Story is… and Episode 64: Nudge, Nudge, Wink, Wink.

What are your thoughts on this? Should “Christian” be a genre unto itself? Why or why not?

Did you find this information helpful? If you did, consider donating.